Explaining the 3 Japanese Writing Systems

If you have ever wanted to learn Japanese, there is one thing you might want to know: Japanese has 3 writing systems. Now they make look similar sometimes, but each writing system has its own quirks that make it unique from the rest. While it may sound a little bit intimidating, we’re here to let you know the Guide to Japanese Writing Systems.

Brief History

The history of the Japanese language is really just a reflection of the history of Japan. Back in the years 300CE, Japan set up the beginning of a lasting relationship with China, leading to a heavy period of Chinese influence over the next centuries. Because the Japanese did not have a written script, they began to use Classical Chinese as a literary language. This gets us to the first two writing systems of Japanese:

Kanbun :

- Kanbun is Japanese in Classical Chinese style, using Chinese characters to stand for the meaning of Japanese words. Later led to Kanji.

Man’yōgana:

- Characters also in Chinese but with the characters standing for the phonetic sound of the underlying Japanese syllables

- Developed into hiragana and katakana to simplify the writing process.

- The biggest use was to annotate Kanbun texts so Japanese speakers could read them.

- Chinese characters stood for the meaning, and the kana supplied the pronunciation, as well as the grammatical elements.

The Writing Systems used today

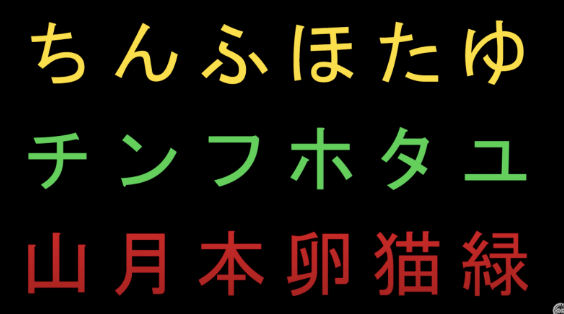

We don’t see kanbun or man’yōgana today, instead, we see the previously mentioned kanji, hiragana, and katakana. However, despite the fact there are three scripts when looking at the photo below, you can see one is clearly not like the other:

Credit: Academia Cervena

Credit: Academia Cervena

Let’s start with the one that stands out from the rest: Kanji.

Kanji: ~54%

Kanji is the writing system left from the Japanese adoption of Chinese characters, with the majority of the characters found within the modern Chinese language. Each character can be made of 2-20 strokes and has nearly 3000 characters within its syllabary. Each character stands for a specific morpheme which usually functions as either a word stem or a word; meaning they are quite content-heavy. Kanji is made up of core words like nouns and verbs.

We can see many nouns written in Kanji, like:

| Japanese | Pronunciation | English |

| 犬 | inu | dog |

| 日本 | nihon | Japan |

| 水 | mizu | water |

The last two are the same characters used in Mandarin to mean the same thing, but with different pronunciations.

| Chinese | Pronunciation |

| 日本 | rìběn |

| 水 | shuǐ |

Hiragana: ~38%

After Kanji, Hiragana is the second most used writing system, with each of its 45 characters being made of only 1-3 strokes. Hiragana acts much more like an alphabet, in the sense every character has one sound associated with it, unlike Kanji where you cannot really guess how a word sounds.

Where Kanji makes nouns and verbs, Hiragana fills out many of the grammar-related words, like prepositions, adverbs, auxiliary verbs & function words. Here are some examples:

| Japanese | Pronunciation | English |

| いつも | itsumo | always |

| あの | ano | that |

| しかし | shikashi | but |

Katakana: ~8%

Finally, we have the third most used writing system, Katakana. Like Hiragana, there are around 45 characters each made with 1-3 strokes. Where Kanji & Hiragana make up core words, Katakana is usually used for foreign words, modern loan words, slang, colloquialisms, and some more technical terms.

| Japanese | Pronunciation | English |

| コーヒー | kōhī | coffee |

| テレビ | terebi | television |

| ハンバーガー | hanbāgā | hanburger |

Loan Words

Finally, there are loan words:

Chinese Characters form around 54% of the total vocabulary, with Chinese characters annotated to be pronounced as they were in Chinese called on-yomi, and Chinese characters annotated to be pronounced as native Japanese words called Kun-yomi.

Additionally, there are gairaigo – Non Chinese loanwords, normally from European languages and written in the katakana alphabet. We can see English becoming the major source of these words, such as the previously mentioned ハンバーガー [hanbāgā]

Conclusion

While the three Japanese writing systems may seem intimidating at first, I hope that this blog has helped in giving you an introduction to the beautifully interesting Japanese language! If you’re looking to get started learning Japanese, with a native-level instructor who will focus on developing your conversational skills one-to-one, make sure you check out our LanguageBird programs! LanguageBird Japanese teachers are here to help you take on this amazing challenge! 楽しい勉強!